March 7, 2012

CONTACT: Fiona Guy fguy@daraint.org (m)+34 678 826 197 (t)+34 915310372

US CONTACT: Meir Kahtan mkahtan@rcn.com +1 212.575.8188

New DARA Research on Humanitarian Aid from Donor Governments Finds Limited Progress; Systemic Issues Persist in Providing Effective Aid – Lives Lost That Could Have Been Saved

Humanitarian Response Index Identifies Persistent Systemic Issues: Lack of Prevention-Oriented Strategies; Insufficient Accountability; Slow Progress in De-Politicization of Aid

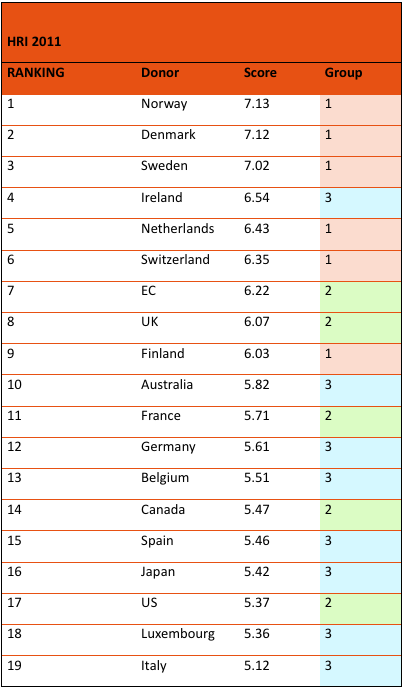

March 7, 2012 – Geneva, Switzerland — While international aid and the ability to deliver to populations in need has improved over time, substantial barriers remain to providing the most needed relief to victims of natural disasters and conflicts, as well as helping them to become less vulnerable to future threats, according to the 2011 Humanitarian Response Index (HRI), released today by DARA. Based on an analysis of the work of 23 donor governments over nine major crises, the Index rates each individual country along five categories, then presents an overall ranking and donor classification (for a table of the 2011 HRI ranking and a non-hierarchical classification that groups together donors with similar strengths and weaknesses, please see below).

The UN’s appeal for $8.9 billion in 2011 to assist some 50 million people facing crises was only covered by 62%, resulting in huge gaps in the response, particularly in helping people recover from crisis situations.

DARA’s report notes that a good humanitarian donor government not only responds to urgent needs, but also focuses on prevention as well as on sustainable recovery, practices risk reduction, is willing and able to work with humanitarian partners, facilitates protection of civilians and respects international law, and holds a commitment to learning and accountability. Observes Philip Tamminga, who led the study, “Without all of these in place, even the best intentions of any government can result in ineffective, inappropriate aid that doesn’t meet the needs of people who need it most.”

A case in point is the United States. While its ability to bring resources to the field is unmatched by any other country, its weaknesses in other areas, such as prevention, preparedness and risk reduction, led to it being ranked 17th on the HRI. Tamminga notes that US government agencies responsible for humanitarian assistance do their best to apply good practices, but other political and bureaucratic constraints often limit the effectiveness of their work. “This is a story of human lives threatened with famine, disease, and violence, and lives that can be saved,” he said. “It should not be a story about government bureaucracy and political impediments to making sure people get the aid they urgently need… and have been pledged.”

While the index placed Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland and the Netherlands at the top of the rankings, no country demonstrated excellence in all areas, with the result that the collective impact is less than it could be. According to the research findings, over the past five years little progress has been made in reforming either the practices of individual countries or the humanitarian response system as a whole. “The result is not only an inefficient use of resources,” says Tamminga. “Lives are being lost that could have been saved.”

The study identified five crucial areas of weakness:

- A reactive, rather than proactive approach– experts estimate that 100,000 or more people, nearly half of them children, died unnecessarily during the famine in the Horn of Africa due to a lack of prevention and preparedness.

- A low priority for gender issues– ignoring that the needs of women, girls, men and boys are vastly different has consequences which range from culturally inappropriate hygiene kits in Pakistan and Bangladesh, to latrines for women in camps with insufficient lighting and security in Haiti and the DRC.

- Inadequate reform agenda– too slow to meet the increasing humanitarian aid burden.

- Minimal donor transparency and accountability-neither decision-making nor allocations are as transparent as they should be in many crises.

- Politicization of aid– security, economic and military agendas take precedence over humanitarian needs in crises such as Somalia, the occupied Palestinian territories and Colombia, hampering aid delivery.

Group 1- Principled Partners: Generosity, strong commitment to humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence, and flexible funding arrangements with partners.

Group 2- Learning Leaders: Leadership role and influence in terms of capacity to respond, field presence, and commitment to learning and improving performance in the sector.

Group 3- Aspiring Actors: Focus on building strengths in specific “niche” areas, such as geographic regions or thematic areas, with aspirations to take on a greater role in the sector.

DARA

Founded in 2003, DARA is an independent organization committed to improving the quality and effectiveness of aid for vulnerable populations suffering from conflict, disasters, and climate change.

For more information, please visit www.daraint.org.

Share this