November 9, 2011

Source: The Guardian

Slow progress at global climate talks is belied by the plethora of actions in many smaller and more at-risk developing nations

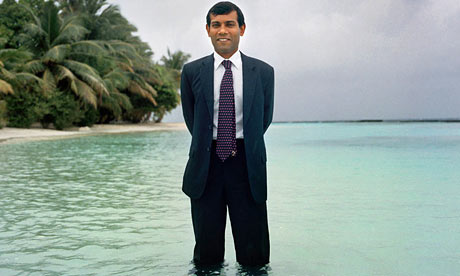

Maldives president Mohamed Nasheed stands in the sea off

As the next round of climate talks – the COP17 climate change conference in Durban – draws close, there is a general air of pessimism about achieving any breakthroughs.

This downbeat outlook comes from a combination of the economic recession in the developed countries with such a level of climate scepticism in the US that everyone knows that Barack Obama’s climate negotiators are powerless to agree to anything in Durban even if they wanted to.

This US role was demonstrated at the recent meeting of the committee set up last year to design the green climate fund to transfer climate aid to developing countries. The committee was supposed to conclude its recommendations prior to Durban but failed to do so when the US delegation objected to a document that most of the other countries had agreed to.

Meanwhile, as the Guardian reported last week, China’s latest overture – an effort to encourage other large developing countries to increase their efforts to reduce emissions – has been met with a mix of scepticism and caution.

But the slow progress at the global climate talks is belied by the plethora of actions on the ground to combat climate change in many of the smaller and more at-risk developing countries.

One particular group of developing countries stands out among them. These are around 20 nations from the three groups that the UN recognises as being particularly vulnerable to climate change: the least developed countries, small island developing states and Africa.

Just before the COP15 climate change conference in Copenhagen in 2009, President Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldives gathered the leaders of around a dozen of these countries and formed the Climate Vulnerable Forum.

The group is not just another negotiating bloc. Rather, it is a proactive group willing to take actions at home regardless of whether consensus was reached at the global talks.

As low emitters of greenhouse gases, their pledges are mainly about taking steps to adapt to climate change, but they have also voluntarily made pledges on cutting emissions.

The most notable of these pledges is President Nasheed’s pledge to make the Maldives carbon neutral by 2020.

Last year, President Anote Tong of Kiribati hosted the second meeting of the Vulnerable Countries Forum where they renewed their pledges to move towards development that is climate resilient and low carbon.

The third meeting of the (by now expanded) group will be in Dhaka, Bangladesh on 13-14 November. It will be hosted by the country’s prime minister, Sheik Hasina, and is expected to be opened by the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon.

They will likely combine their existing pledges with poverty alleviation, agreeing to act regardless of whether a global agreement is achieved in Durban in the following weeks.

These poor and vulnerable countries realise that their contribution to greenhouse gas emissions is tiny, and their efforts to reduce them will not slow down climate change by much.

They are making that commitment not because they have to, but because it is the right thing to do and because every little bit counts. They are hoping that the richer countries – as well as big emitting developing countries – will follow their lead.

When the UN talks get underway in Durban in three weeks, and the United States and China resume their game of who-blinks-first, other countries are realising that they need to act before that game ends.

• Saleemul Huq is senior fellow in the International Institute for Environment and Development’s climate change group.

Share this